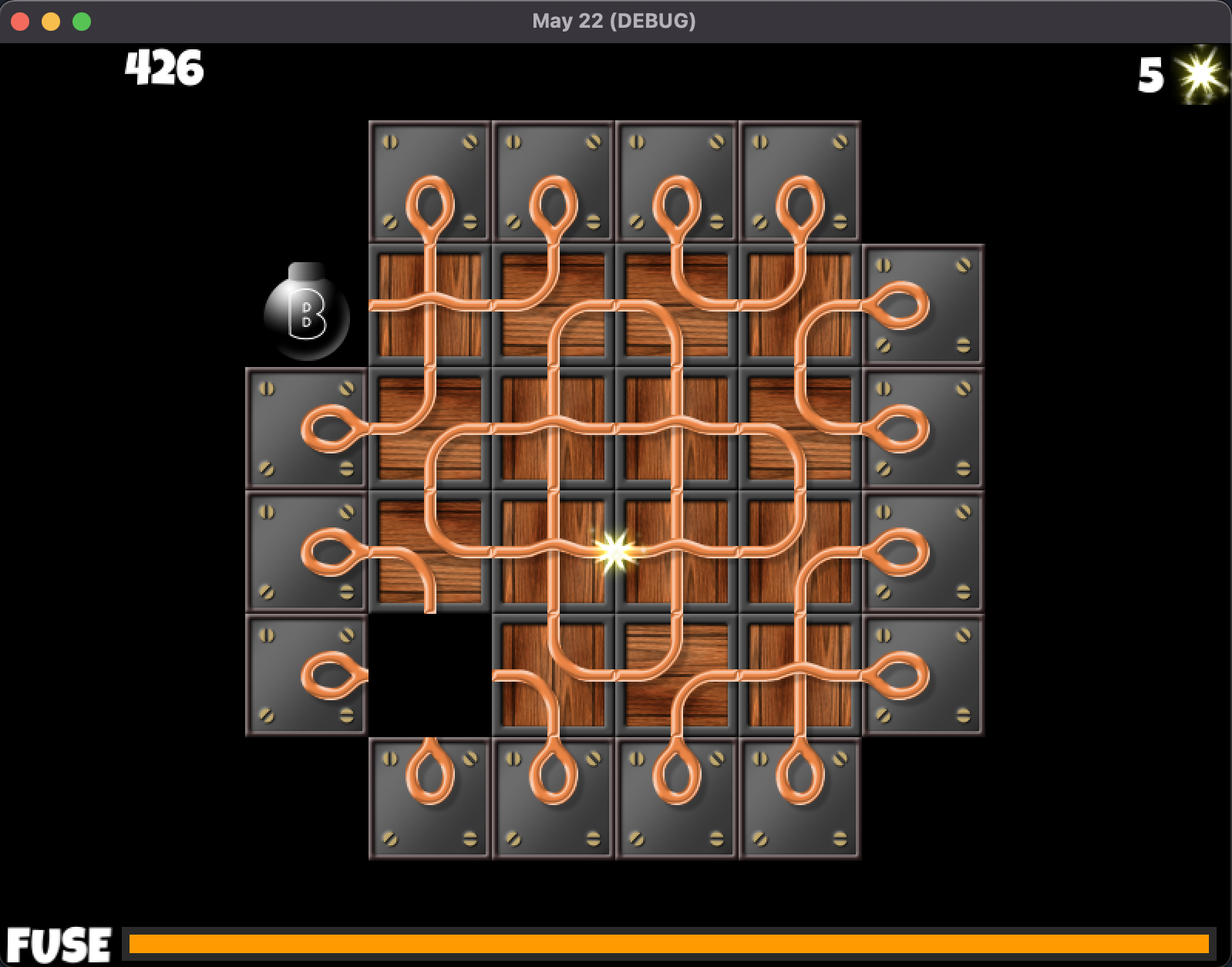

Day12: I’ve been spending what time I can spare on the game polishing various parts to make the whole thing a lot more complete.

Level building animation has been added, so the level doesn’t just appear anymore, but animates nicely into place. Same for level failed, when the spark fuse runs out, the board disappears in a fun way too.

I’ve also been tweaking the graphics, creating some nicer tile bases, and including a couple of variants, the plan is to have a few variations of the tile designs that can be used in different levels, much like the original game changed the colour combinations between levels.

The most unexpected, and in many ways, fun and satisfying change this time is the initial inclusion of an in-game level editor. Yeah, I know, time is tight, doing this in a month, it seems that writing level editors is a bit of an unnecessary luxury, but I did think about it. Entering the level details by hand for each of the 64 levels was going to take around 10-15 minutes each, or 16 hours, not to mention is mind-numbingly boring. I figured a simpler visual tool for placing the tiles and setting the various parameters could realistically reduce that to about 5 minutes per level, transcribing from the map file, a total of 5 hours 20 minutes. Given that the editor has so far taken less than 2 hours, that’s a saving of 8 hours 40 minutes, so worth it, and as I said, it was fun.

The key to the ability to build an editor in such a short amount of time is the inherent separation of the core design, the board is an object, each tile is an object, and each of these elements are self contained, with little to no knowledge of each other or how they work, just a simple exposed interface. This meant that I could drop a copy of the board scene into another scene, the level editor, and with just a few small changes, have it work as I desired. Alongside the board, a simple editor object overlays a grid, and takes care of mouse input to determine where the user has clicked and make changes to the board. One cool thing is that the board object has code already to build and teardown the board tiles, code that is used during play when switching to a new level. In the editor, I used this as an initial, brute force, way of editing. Each time the user clicks on a cell in the board to change the tile type, the code modifies the cell tile identifier in the level definition object, a simple 2D array of integers representing the tile types, and then tells the board to rebuild the whole thing, tearing down and disposing of all tiles, and the recreating them all, along with the modified cell. This might seem over the top, but as the board is never going to be more than 9x7, including the surrounding cells, it is perfectly fine, it is instantaneous. So no complex code needs to be created to remove an individual tile, create a new tile and place it a the correct position on the board, just a single call to “build_level” and all is good. A proof for the mantra, “always avoid premature optimisation”, if the brute force approach works, and a more optimised solution offers no meaningful benefit to the end user, then it’s fine.